For its seventh edition and interpretation of “what is Italian design”, the Triennale Design Museum in Milan has picked a very topical theme: crisis…

Italian design beyond crisis. Autarky, austerity, autonomy: 7th edition of the Triennale Design Museum. Museum/exhibition (April 4, 2014 – February 22, 2015): director Silvana Annicchiarico, curator Beppe Finessi with Cristina Miglio, in collaboration with Matteo Pirola, Annalisa Ubaldi. Exhibition design by Philippe Nigro. Graphic design by Italo Lupi. Catalogue: edited by Beppe Finessi, layout by Italo Lupi, Mantua: Corraini, 2014. 400 pp. Ill. ISBN 978-88-7570-449-0, € 50.

For its seventh edition and interpretation of “what is Italian design”, the Triennale Design Museum in Milan has picked a very topical theme: crisis. As explained by the museum’s director, Silvana Annicchiarico, the inspiration came from the idea that crises “can sometimes be healthy” in that they stimulate creativity. The working hypothesis that was therefore proposed to Beppe Finessi – who curated the show with Cristina Miglio, in collaboration with Matteo Pirola and Annalisa Ubaldi – was to check if and how the Italian “culture of design has been able to transform into opportunities constraints, pressures and limitations generated by crisis”, in short, what Italian design did do “when it found itself operating in a society ‘with its back against the wall’” (p. 23).

The curators decided to focus on three major, full-blown moments of crises in Italian and international history: the current global crisis; the crisis of the 1930s which was marked by the Fascist politics of autarky; and the austerity period of the 1970s that followed the oil crisis. Autarky, austerity and autonomy (in Italian the third term actually reads as “self-production”, i.e. “autoproduzione”) appear in the subtitle of the museum and mark the tripartite articulation of both the museum and the catalogue. However, the curators chose to expand the boundaries of each phase and to eventually embrace, in their examination, a more extended period of years. Hence, the first section spans from the 1920s to the 1960s, the second remains focused on the 1970s, while the third begins with the mid-1980s and closes with the present day.

In addressing this more extended period, which includes the decades when a modern culture of design properly formed and developed in Italy, the curators decided nonetheless to avoid the most famous and iconic image of Italian design, pursuing instead an “alternative” history (an adjective on which Finessi insists) made up of “many seemingly minor incidents, often forgotten, of craftsmen artists, female figures that have always been able to make much with little, and small production companies capable of acting freely in search of new languages and new markets” (p. 29). Given the working hypothesis, mentioned above, the curators’ argument behind this edition of the museum seems, from the start, to be that design culture’s response to crisis, or one of its possible manifestations, resides far from industry and mass production, and instead in crafts, small production and so-called self-production. In other words, that the answer is in a certain idea of “futuro artigiano” (i.e. “future craftsman”, this well-known expression by Stefano Micelli is used by Finessi; in the catalogue, however, the English translation reads “the craftsman of the future”), an idea to which this edition of the Triennale Design Museum indeed gives support by finding and displaying its possible “forerunners”, its fathers and mothers, and its actual children.

Focusing on furniture, interior decoration, home accessories, with some inlets for clothing and fashion, jewelry and, to a limited extent, architecture and graphics, the curators brought together over 600 pieces – primarily products, but also some sketches, technical drawings and photographs – from a long list of lenders, including museums and archives such as Mart, in Rovereto, and CSAC of Parma, as well as many private lenders (the designers themselves for the recent pieces).

The landscape of materials thus collected is certainly impressive and capable of revealing to the public, even to specialists, a lesser known and recognizable picture of Italian design. A striking sneak preview of this picture is offered in the entrance hall of the museum and in the opening pages of the catalogue, where pieces from various decades are introduced, among which: an autarkic bike (1939), a version of the straw chair conceived by Alessandro Mendini in 1975, a wedding dress made of pieces of undergarments sewn together by Pietra Pistoletto (1996), the spectacular wire animals by Benedetta Mori Ubaldini (2003-2014), the “flying” office built out of an industrial pallet by Lorenzo Damiani (2004), and the Autarchy series of bowls by Formafantasma (2010).

Beyond the entrance hall, the visit begins with a dark room dedicated to Depero and the productions of his art house, often made by female hands, and closes with another dark room, devoted to “digital design” and, in particular, to the work of Denis Santachiara.

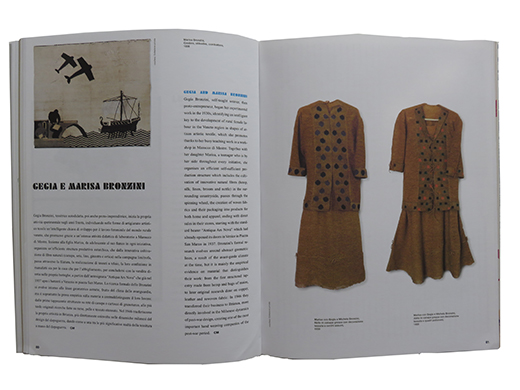

The first section, “From autarky to autonomy” presents, among others, furniture, clothes and fashion accessories made of autarkic and local materials, and produced in various regions of Italy by artisans such as Cesare Andreoni, Bice Lazzari, Gegia and Maria Bronzini, and Anita Pittoni; furniture designed by Gio Ponti for the Montecatini building he also designed, but also “his” papier-mâchés and “his” enamel animals, manufactured by skillful craftsmen; the coeval and yet diverse lines of Carlo Mollino’s and Franco Albini’s furniture; pieces made of reed, rattan and cane; lamps of cut-out aluminum made by Ettore Sottsass, as well as a tapestry and ceramics he designed in the postwar years; the decorative lithographs by Fornasetti and the sophisticated, essential, shapes of the pieces “edited” by the Danese company; ceramics of different sorts, from the “aristocratic” household products by Fausto Melotti, to the serial ceramics by Antonia Campi and by Roberto Mango, and the research pieces by lesser known figures such as Marieda Boschi di Stefano and Rosanna Bianchi Piccoli; home fabrics and tapestries by Fede Cheti and Renata Bonfanti; the unique invention of Renato Vengoni’s vehicle, built of Vespa components, and the reproducible creation of the sun-visor glasses designed and patented by Bruno Munari.

The second section, “From austerity to participation”, displays a more limited number of projects. In addition to examples of Riccardo Dalisi’s “poor technology”, furniture based on Enzo Mari’s “Proposta per un’autoprogettazione”, and the Golgotha chair by Gaetano Pesce, one finds documentation of the visionary habitats of Paolo Soleri, of the ingenious and ironic urban interventions of Ugo La Pietra, of Sottsass’s “Metaphors” (experimentations of space and construction in the natural environment) and of the Global Tools’s workshops, as well as some of Giancarlo Iliprandi’s civically-engaging posters.

Finally, in the third section entitled “From self-production to self-sufficiency”, displayed are the Animali domestici by Andrea Branzi – furniture pieces made of assembled natural and industrial components – and a number of “private” and “small” production pieces by such “masters” as Mendini, Pesce, Dalisi, and Michele De Lucchi, and, again, Sottsass, followed by an abundance of furniture pieces, gadgets, experimental and more or less provocative objects that combine and explore the aesthetic and conceptual implications of traditional materials like marble, glass, wood as well as components of recovery, of craftsmanship and cutting-edge technologies: projects conceived as one-off pieces, small series, or designs ready for download and on demand reproduction by successive generations of designers, some of whom are categorised only as “young”, others as “new masters”, some of them Italian but not active in Italy, while others, still younger, are Italian by birth but operating abroad, like Martino Gamper and Formafantasma.

The array of materials on display in both the museum and catalogue is vast and such that one cannot approach all of them with the same abiding attention in the same viewing. Compared to the catalogue, the actual museum visit posed quite a challenge as no breaks were offered along the substantially linear path.1

Certainly, the amount of pieces posed a challenge to Philippe Nigro, the exhibition designer, too. His solution entailed creating a sort of “road” (p. 393), a setting that – in order to reflect the theme of the museum – was built in panels of reconstituted poplar wood (a material generally used for packing cases), painted white on one side and left partially exposed on the other, and, in some cases, intentionally unfinished. Along the sides of the “road” – in particular in the first and third sections – walls, showcases and niches rise, as well as terraces that support the display of aggregations of items. Furthermore, at various points, small rooms open that are dedicated to designers and manufacturers (Depero, as mentioned before, Mollino and Albini, Danese), single projects (in the first section, the Montecatini palace), places (Turin, Sardinia), as well as materials and techniques (in the third section, the mosaic, the Carrara marble, and “digital design”). In correspondence with the second section, the path opens around two large display elements hosting the projects from the 1970s.

The graphic design of both the catalogue and the exhibition was created by Italo Lupi. In the catalogue, the insertion of butcher-like paper, to mark certain texts, recalls the colour of the installation exhibit.

Exhibition and catalogue essentially correspond in content, with slight differences. The introductory texts and the shorter texts that accompany the items on show almost coincide with those in the catalogue where, however, they are signed – mostly by Miglio, Pirola and Finessi. For the first part of the museum/catalogue these texts are a good balance of evocation and information – apparently they rely on an existing literature of studies and catalogues but, unfortunately, such sources go unmentioned. The tone changes, however, as the authors approach the more recent and contemporary stories/cases: here the texts appear more vague, hunting for labels and trends (e.g.“masters”, “the young after the masters”, “new masters”, “neo-primitivism”, “low cost” etc.), adhering to the poetics of this or that designer, flowing with allusions that suggest and evoke but never really explain. Along with these texts, the catalogue also includes essays by other authors and scholars: Cristina Michail Tonelli and Giampiero Bosoni, who introduce, respectively, the autarkic and austerity periods; Fulvio Irace, who discusses Ponti’s design of the Montecatini palace and interiors; Giancarlo Iliprandi and Stefano Casciani evoking, in a personal manner, the Pianeta Fresco and Ollo magazines; Anty Pansera, who follows the “pink” thread of women’s presence in Italian design and crafts; Domitilla Dardi, who attempts to bring clarity to issues of craftsmanship, self-production and the makers movement; and Aldo Bonomi on Italian industrial districts. Finally, the captions accompanying both the pictures on display as well as those in the catalogue (just in Italian) provide only the names of the authors, the titles of the pieces/works, the dates and the names of the manufacturers, and omit any information on materials or manufacturing techniques – information which, given the theme of the museum, would have been interesting to find.

In visiting the museum and flipping through the pages of the catalogue, one has the impression that the curators’ intention was not so much to develop a coherent narrative or interpretation of the topic of design at the time of crisis, but rather to collect and present an abundance of cases and stories individually related, or that could be variously connected, to a broad notion of crisis. This notion, though, apparently fades and recedes into the background, and the criteria of the selected and organised content appear vague. As mentioned above, the concentration on three periods of crisis is diluted over a broader arch of time and veers away from the initial focus. The decision to focus on products limits the understanding of their differences in relation to the issues put forth. In presenting pieces in a close sequence and in a invariant manner – as for example such pieces from the first section as the ceramic wall panel by Guido Gambone, the “murrina” produced by Venini in Murano and under the artistic direction of Carlo Scarpa, the lace designed by Fornasetti and made by skilled women embroiderers, the metal outputs from the hand of Sottsass, the series of bowls made of extruded ceramic experimented with by Roberto Mango and the rattan furniture elements designed for mass production, the Danese “editions”, as well as the patented glasses by Munari – one risks suggesting that they are all equivalent, while, in fact, they are quite different in terms of intentions and production contexts, not least with regards to the role played by design and designers.

In many cases, moreover, it is difficult to follow the curators’ criteria for selecting pieces, as they oscillate between emphasising, alternatively, crisis as poverty/lack, local/national identity of materials or manufacturing, and “self-production”. The latter concept, furthermore, is rather generically understood and used quite indistinctly to describe the work of both the contemporary designer (who chooses to devote her/himself to one-off pieces, good for the art/design market) and the artist craftsman from the early twentieth century (who could only use what s/he finds available nearby). Also, weighing on the choices made by the curators, is the declared intention to trace an “alternative” history, played out by chasing the peculiar and the lesser known/seen. So, for example, the presence of some journals seems disjointed from the crisis issue: while the explanation for including Stile, directed by Ponti, is that it was published during the war, Pianeta Fresco and Ollo seem to be included for the mere fact of having been produced by a team of few people. Even more pretentious is the inclusion, in the third section, of relatively private pieces, such as a chair decorated by Lisa Ponti, and the New Year’s greeting cards personally made by Iliprandi and Sottsass. The same holds true – without, of course, detracting from the beauty and poetry of the project – for the book by Munari devoted to the “sea as craftsman”. Finally, some of the insights offered along the “road” and in the catalogue are confusing, for instance, again in the third section, the focus on materials and techniques such as marble and mosaic. In order to evoke the question of crisis, for example, the mosaic is reported as having been born as a poor technique, yet the catalogue and exhibition go on to highlight its appropriation by designers such as Mendini and Fabio Novembre (see the inclusion of his sumptuous designs for Bisazza’s showrooms in the catalogue) which apparently talks little of poverty or crisis; they rather talk of luxury, a concept which is certainly not incompatible with crisis, but is never mentioned or discussed by the curators.

Ultimately, the seventh edition of the Triennale Design Museum – apart from what its title, and the titles of its sections and some texts, here and there, seem to suggest – clearly does not illustrate the answers offered by design culture and designers to a society in crisis. After all, when viewed as a whole, the various furnishings, gadgets, and “conversation pieces” that abound in the final section might cause one to think or to worry that design has little to offer to a society “with its back to the wall”. However, if the museum’s curators never really intended to address the topic of design’s answers to critical situations, they have also not even succeeded in transmitting the broader theme of crisis as lack and as opportunity for creativity. From this point of view, one could say this edition of the Triennale Design Museum has indeed missed an opportunity. In fact, the idea that modern design was born, and has developed, in Italy within a condition of economic, social and cultural crisis is probably one of the most repeated topoi about Italian design and made in Italy in general – with two variants: the negative (that design in Italy developed notwithstanding a condition of crisis and deficiency, particularly in the industrial sector) and the positive (it developed thanks to that condition). This is a commonplace idea that deserves to be reviewed critically.

Anyone who visited the 7th edition of the TDM could not have missed, upon leaving the exhibition, the first installation of the Icons of Italian design, the new permanent area dedicated to “what remains”, beyond trends and school, and settles in people’s imagination and perception as a “classic”. To be confronted with the icons of Italian design immediately following the immersive landscape of handcrafted, non-industrial and non-serial items may have seemed reassuring to some, like the return to order after a digression, whilst ironic to others, like the revelation of a joke. Yet it is precisely when one compares the names of the designers of those icons with those names featured in the exhibition, and discovers that many coincide, and also when one recalls the stories of “crisis” that are behind the production of many of the so-called icons – the Vespa, to name just one – that s/he finally realises that, ultimately, all of the exhibits, in both the semi-permanent exhibition and in the permanent collection, are but the twisted faces of the same history. A significant reminder that, rather than “alternative”, all those faces and stories have in fact co-existed alongside one another and penetrated one another, and that perhaps they should be examined as such, and not in isolation.

Note

- In this edition of the museum a space for resting and reflection would have most certainly been appreciated, perhaps even more than in the previous one, The syndrome of influence (curated by Pierluigi Nicolin, April 6, 2013 – February 23, 2014), for which at least some tables and seats had been placed two-thirds way along the visiting path to allow visitors to sit, rest, and browse the catalogue. With regards to this common problem of many design museums, see Elizabeth Guffey’s interesting piece written a few years ago in designobserver, September 30 2013).↵